Opening ≠ opening

Forms, opportunities and disadvantages of open science

With the first scientific discovery, the conflict arose between the right to ownership of intellectual property and the fundamental principle of science to share these results and thus to further drive the creative, collaborative process of creation. Now that we have arrived in the information age, the question arises all the more urgently: How do we deal with research findings? One possible answer is open science.

In the early days of science, research was mostly carried out by individuals, philosophers or universal geniuses interested in nature. There was already lively exchange in ancient times, and the forum was the meeting point for public discourse. In the Middle Ages, monasteries in particular were the centers of education and research. It was here that Latin established itself as the language of science at the time. With the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in the middle of the 15th century, writings - including scientific texts - were made available to a broad public for the first time, and information became generally accessible. With the Renaissance in the 17th century, the scientific method was developed, which system introduced into the research process (cf. the opposing positions of Newton (1726) and Descartes (1637)).

The Age of Enlightenment began around the 18th century, and with it universities gained in importance again. From the middle of the 20th century, the focus of the universities changed: instead of an education system for the elite, it became one for the general population, and the university became a key institution of modern society. In addition to the universities, a large number of other institutions emerged, for example technical colleges or adult education centers. However, the growth of these educational institutions also resulted in a dependency on state resources or private funding. This has jeopardized the independence and freedom of research in these areas (Perkin, 2006).

Against the background of this threat, which is still current today - namely that science could take a step backwards again, that specialist knowledge could again become an exclusive good for a small part of the population - many scientists are looking for ways to gain access to research to open - with the aim of an open science, expressed with the catchphrase Open Science.

Friesike and Bartling (2014) state that there was no suitable scientific publication system until the 17th century. This led to research results being communicated in encrypted form within the scientific community. Only those people who had the same level of knowledge understood the news. Since research is always based on other research, this has of course been a major obstacle to innovation.

It was only the system of scientific journals in which research could be published that guaranteed scientists a right to their ideas and thus formed the cornerstone of modern research. With the emergence of this system - also known as the “first scientific revolution” - the costs of publishing research results fell significantly. The entire publication system is based on these articles, which are actually intended for printing. According to Friesike and Bartling, the internet now offers possibilities that would have been unthinkable a few years ago. These diverse new methods, which have names such as Open Science, Open Research or Science 2.0 depending on their goal and origin, could provide for a “second scientific revolution”.

1. The diversity of open science

If you carry out an analysis of search queries on Google for the term “open science”, you can see that interest in it has increased steadily on average over the past decade. So the topic is brand new.

Open science can take many forms, the term is not clearly defined. Depending on which area you focus on most, five streams of thought can be identified. The different areas would be the basic technological structure of open science, the accessibility of processes for creating knowledge, alternatives for measuring scientific influence, democratic access to knowledge in general and research in the community (Fecher & Friesike, 2014).

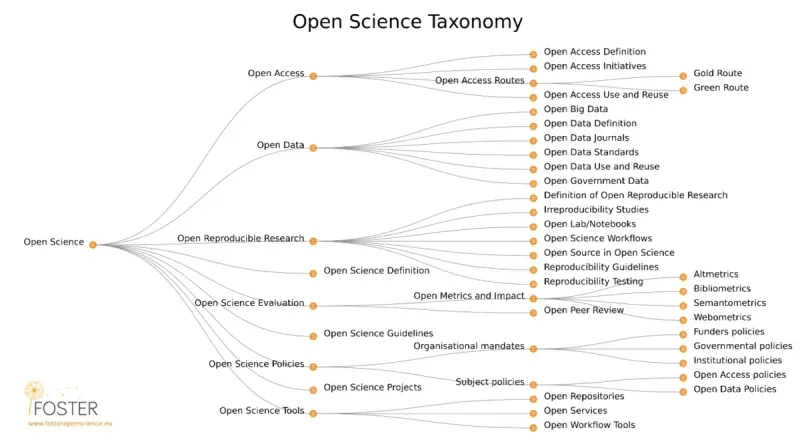

The tree structure that Knoth and Pontika (2015) created shows how diverse the field actually is:

Figure 1: Hierarchical classification of the terms based on Open Science; Knoth and Pontika (2015)

**

**

Vicente-Saez and Martinez-Fuentes (2018) used literature research to search various databases for studies that contain the term "Open Science" and that were written in English between 2006 and 2016. They analyzed this and came up with a clear description:

Open Science is transparent and accessible knowledge that is shared and developed through collaborative networks (Vicente-Saez & Martinez-Fuentes, 2018, p. 428)

Using two of these many forms of Open Science, we will now go into more detail about their characteristics, advantages and disadvantages.

1.1 Open Access - open access to knowledge

Some of the aspects mentioned above can be found in the above description. The phrase “accessible knowledge” is particularly striking, pointing to one of the most important principles of open science and which is perhaps also most often associated with it, namely open access.

In times when journals were only available in printed form, Open Access was neither practical nor economically feasible. It was only with the rise of the Internet that there were opportunities to make access to knowledge barrier-free. This development was also driven by a financial crisis in scientific journals around the 1990s. For many years, the cost of subscriptions has increased much faster than would have been justified by inflation. At the same time, the accumulated knowledge grew - and grows - faster than the budgets of libraries (Suber, 2007).

All of this resulted in the open access movement gaining momentum. The declaration of the “Budapest Open Access Initiative” in 2002 represents a milestone, with which the central standpoints of the movement were summarized and through which Open Access gained public awareness through well-known representatives (Budapest Open Access Initiative | Read the Budapest Open Access Initiative, 2002).

In general, according to Suber (2007), a distinction is made between two paths in Open Access. On the one hand there is “gold open access”, where the articles are published in open access journals, for example in the “Public Library of Science”, PLoS. One advantage is that publications - as in journals with the classic model - are peer reviewed. The cost of publishing usually has to be paid in advance by the person submitting the work, i. H. by the scientist or the institution behind it.

Another route of open access would be “green open access”. The articles are published in journals with restricted access, but at the same time also stored in so-called "Open Access repositories". These archives can be organized by area or by the university that maintains them. A well-known example would be “arXiv”, where preprints from the field of physics are published.

Open Access brings numerous advantages for all stakeholders involved. The authors have a larger audience, their work has a bigger impact. The readers are given barrier-free access. Teachers and students in particular have access to knowledge, regardless of their financial or social position. This in turn makes it easier for them to generate new knowledge. Journals, but also universities, receive more attention and weight if they take an open access path. Last but not least, the citizens also benefit, as this gives the entire population an insight into the research that it finances indirectly with its tax money. Because Open Access drives the innovative research process, the general standard of living can be raised (Suber, 2007).

The role that open access to scientific work plays with regard to global social justice should not be underestimated. To cope with many of the challenges currently affecting developing countries (e.g. poverty, inadequate hygiene, hunger or illiteracy), education and advances in science are necessary - not for a small number of experts, but for the general population. In order to guarantee everyone's human right to education, care must be taken to keep access to scientific resources as barrier-free as possible. In addition, the production of research results is very unevenly distributed around the world. Over 80% of the most frequently cited publications come from just eight nations (Chan et al., 2005). The reverse is that there is a huge, as yet untapped potential for research in developing countries.

1.2 Citizen Science - anyone can do research

Another important point in opening up science is the collaboration of several scientists from different disciplines and parts of the world on a problem. Of particular importance, especially in the recent past, is the collaboration between academically trained scientists and interested laypeople. This is summarized under the multi-faceted term Citizen Science, which according to the "Green Book Citizen Science" is defined for Germany as follows:

This citizen science already has a long tradition. Especially in the field of ecology and research into the environment, the roots of citizen science go back to the beginnings of modern science. The big advantage nowadays, however, is that the general public - potentially anyone with sufficient interest - can participate in such projects. This has been made possible by innovative tools that make the exchange of information much easier. Above all, the Internet should be mentioned here, but mobile hardware (smartphones, for example, are powerful and versatile computers) and easy-to-use software also play a major role here. Some scientific projects would not be possible without the enormous amount of free work that citizen scientists provide (Silvertown, 2009).

This can be illustrated well using the example of the “Earthwatch” project. The NGO "Earthwatch Institute" researches nature conservation in the rainforests. However, the field research associated with this requires a large number of volunteers. Citizen Science made it possible for researchers to gain around 13,000 hours of work performance for the people involved through 2,300 hours of training from 328 volunteers, which corresponds to more than five times the time invested (Brightsmith et al., 2008).

In addition, there are a few other advantages. In general, it is blowing a breath of fresh air into some of the outdated scientific structures. As different as the individual citizens are, so are their views and perspectives on problems and thus also their approaches and strategies. It also stimulates discussions when the participants come from different areas of life. The “Citizens” themselves also benefit from participation, on the one hand through direct involvement, which satisfies intrinsic needs. On the other hand, also by the fact that the citizens in this way their specific problems affecting them to decision-makers, e. B. from politics, can apply (Bonn et al., 2017). Politics, science and society should not be separate, separate areas, but rather, just as they are confronted with common problems, they should also work together to solve problems.

2. An opening with challenges

An opening of science also means that some established systems and well-established behaviors have to be adapted, and possibly even replaced. Such a change naturally also brings with it some challenges. Resistance is to be expected from journals with a classic publication system, whose business model is based on subscriptions and which therefore see their existence threatened by Open Access. It is also often feared that there could be conflicts with copyrights. According to Suber (2007), however, there is no danger here because the rules customary in science apply and are observed.

On the contrary, Open Access could even help to secure the rights of authors to their own articles, because according to the traditional system, copyrights are transferred to the respective publisher when they are published - a model with which few scholars are happy. To find a solution to this sensitive issue, some novel copyright models have been developed (Hoorn & van der Graaf, 2006).

It should also be noted that even with open access there may still be barriers, for example censorship, language barriers, "accessibility" problems or even a lack of internet access (Suber, 2007). This fact makes it clear that Open Access alone cannot overcome all existing obstacles, but is only one way of dealing with science in the information age. "Good practices" have also been developed to help in this area, which are intended to enable the correct use of Open Access (see, for example, Good Practices for University Open Access Policies - Harvard Open Access Project, 2020).

There are also challenges in the area of citizen science. In principle, the same problems can arise here as with conventional research. The correct handling of scientific data has a steep learning curve, and in the case of Citizen Scientists, the quality of the data obtained could be lower than it would be in the case of experts due to a lack of training. In order to keep the random error to a minimum, it is therefore important to take suitable countermeasures. Although its extent is reduced by the mostly very large data sets, the measured values should always be checked by experts (Dickinson et al., 2010).

In addition to this random error, systematic influences can also have negative effects on the research results. In particular, spatial and temporal sampling bias, i. H. falsified sampling, according to Dickinson et al. (2010) poses a problem. For this reason, it is important to adapt the task to the respective volunteer and to use randomization in the allocation. Further measures to ensure the quality of the data would be to only consider those that come from citizen scientists who have been involved for more than a year, regularly participate in projects and deliver error-free results.

There are also guidelines and guides for Citizen Science projects to support them, e. B. that of the "UK Environmental Observation Framework" (see Pocock et al. (2014)). This guide accompanies scientists who want to create a Citizen Science project through the individual phases. He also provides some case studies and helps with the question of whether Citizen Science is the best approach to a particular problem. Finally, it also provides links to citizen science networks that are designed to facilitate the exchange between researchers.

3. Open to the future

With the expansion of the Internet and the emergence of new technologies, we live in an increasingly networked world. Access to the Internet and thus also to the many opportunities to exchange ideas with people all over the world is easier than ever in most places today. The rise of social networks further reinforced this trend. Voytek (2017) argues that social media, open science and data science are part of a major transformation, not independent phenomena. In this way innovations are created, which in turn fuel new innovations - a positive dynamic is created.

Especially in times of a pandemic, which affects almost all of humanity, the great advantages of preprints have also become apparent, which accelerate the progress of research in this area, as they can be viewed before the peer review. During a crisis it is important that as many researchers as possible are up to date with the latest knowledge. This is mainly made possible by the rapid publication of the preprints. While even less well-checked studies are initially visible to the public, the open discourse enables errors to be recognized at an early stage and studies with errors to be withdrawn earlier. Ultimately, many of the preprints later go through the peer review process and thus contribute significantly to research (Majumder & Mandl, 2020).

Since the topic of Open Science is very topical, there are still many debates about the various advantages and disadvantages. But the greatest risk, as Shaw (2017) puts it, could be if we do not use these powerful tools to our advantage.